Business

What a Joe Biden presidency will mean for South Africa’s economy

I’m sometimes surprised by the extent to which South Africans are fascinated by the US elections, but given the country’s continued dominant status in the world, its importance to us as a trading partner and its undeniable cultural influences, I shouldn’t be.

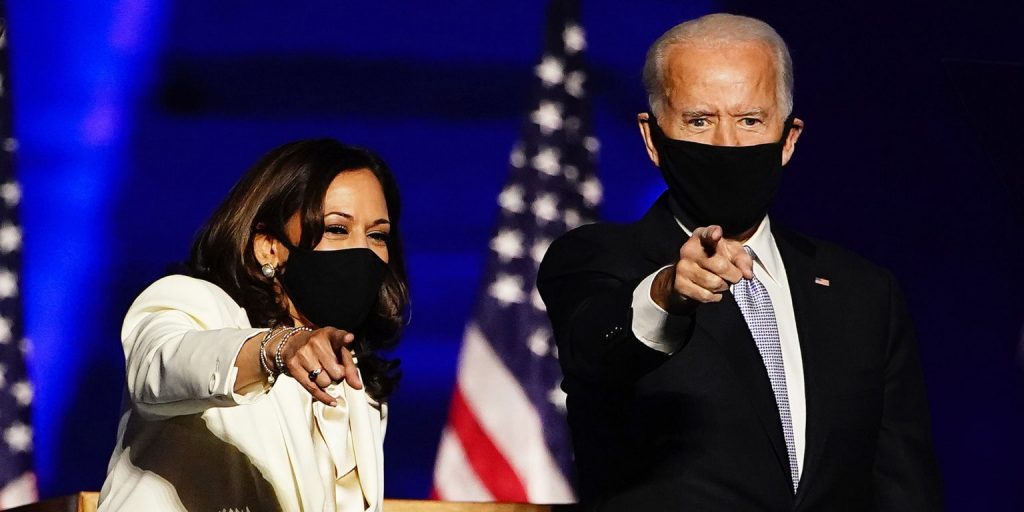

Vice President-Elect Kamala Harris (L) and President-elect Joe Biden as he arrives for for his victory address after being declared the winner in the 2020 presidential election in Wilmington, Delaware, USA, 07 November 2020. (Photo: EPA-EFE/JIM LO SCALZO)

We are not alone. After a week of high drama, global audiences have unglued themselves from their screens and have resumed life as they knew it – to the relief of Amazon, which saw orders decline over the period.

Joe Biden and Kamala Harris are the president-elect and vice-president-elect, respectively, of the US and now the focus has shifted to wondering what the Democrat victory could mean for South Africa and Africa.

Certainly, during Donald Trump’s term in office, South Africa was not on the US radar. The US president did not visit the country, made references to “shithole countries” and took two years to appoint US ambassador Lana Marks to her post.

While the US was idle, China increased its footprint across the continent – a fact that was not lost on the Americans.

For many, the Biden victory has been welcomed as it carries hopes of renewed US focus on Africa. I do believe this will be the case – Africa has the world’s fastest-growing population and is the site of future global growth. But it will be different, and both business and government need to understand this if they are to take advantage of any opportunities.

The US has shifted its approach to trade and foreign policy in recent years. This shift was interpreted and expressed by Trump in his typically obnoxious fashion and resulted in a trade war with China that was an unmitigated disaster. The US trade deficit with China, which precipitated the dispute, is now back at the record levels of 2008.

But instead of rolling this policy back completely, I think the Biden administration will refine it. Bear with me.

For most of the past 100 years, the US has entered into trade negotiations believing that open markets foster democracy, which in turn supports the maintenance of world peace. In this way, its trade policy and foreign policy were inextricably intertwined and trade was used to reinforce foreign policy objectives.

It appears that this is no longer the objective of US trade policy.

Alan Wolff, the deputy director-general of the World Trade Organisation, says that under Trump, US support for the postwar international economic system shifted, evidenced by the US’s withdrawal from the Trans-Pacific Partnership in 2017 and the Paris Climate Accord in 2020. If this did not attract attention, then it was Trump’s belligerent efforts to provoke a trade war with China that did.

If democratic outcomes are no longer the raison d’être of US trade policy, then the basis of US support for the multilateral trading system will now be found in pragmatism and in narrower commercial self-interest.

I’m not passing comment on whether this is a good or bad thing – it could be either – but at least we all know where we stand.

The emphasis, then, is on rebalancing skewed trade relationships and on relationships of mutual benefit. This is a policy that resonates with millions of American voters who are bothered by their own (perceived) failure to benefit from globalisation.

Biden and Harris have the twin task of rebuilding a fractured society while reclaiming the US’s leadership on the world stage.

I believe their policy stance, initially, will be more measured than many on the left would like. Biden will resume negotiations with China in a bid to ease trade tensions – it is in the US’s interest to do so. This has positive consequences for global trade, and for South Africa, which was caught in the fallout – the US’s higher tariffs on steel and aluminium was just one example.

Biden will be looking to present a united front in US negotiations with China and will seek to strengthen US relationships with both developing countries and stronger nations, rejecting the Trump administration’s go-it-alone mindset.

South Africa and her SADC partners need to be prepared for this.

At this point, I don’t think there is any threat to the African Growth and Opportunity Act, which gives sub-Saharan nations greater access to the US market and allowed South African exports of more than $7.5-billion to the US in 2019 alone. But much could change before it is renewed in 2025.

South Africa is expected to be a major contributor to and beneficiary of the African Continental Free Trade Area. Expectations are high that a Biden administration would see more recognition and support of intra-Africa trade as opposed to Trump’s focus on bilateral agreements. This has the potential to boost South Africa’s economy.

Foreign policy is an area in which Biden has considerable expertise and skill and there is some consensus that the US will demonstrate renewed leadership on the global stage – but this will not be unilateral. Other countries will be expected to step up to the challenge of acting in the best interests of maintaining and enhancing the world trading system. They will do this because they will find that it is in their geostrategic and their economic interests to do so. BM/DM